How CW&T Built a Sustainable Design Studio Over the Course of a Dozen Kickstarter Campaigns

The couple’s successive campaigns and thoughtful communication have helped them grow a dependable audience.

The Creators

CW&T is the art and design practice of Che-Wei Wang and Taylor Levy. They’re designers’ designers, known for artfully simplistic pens, tools, watches, and sketchbooks. They’re also a married couple with young children, and do much of their design work from a studio in the basement of their Brooklyn home.

The Project

Their Herring Blade project is “a super low-profile utility knife for single handed operation and everyday carry,” available in variations for both righties and lefties. It’s a classic example of the work they’ve built a reputation for over 11 previous campaigns: a very pared-down, practical design that anticipates the understated features a user will need.

The Budget

Goal: $5,000

Time to goal met: 1 hour

Raised: $73,995

Backers: 688

Levy and Wang start budgeting while they’re prototyping. “It’s a way to think about a project,” Wang says. “If it involves multiple parts, it's a way to organize where to source each thing from, or even which parts to design.”

He makes a spreadsheet financial model calculating various potential total costs based on vendor options, order quantities, and contingency plans. For example, one vendor might charge $2 a unit for a minimum order of 1,000 units, while another is willing to take orders of 100, but for $4 a part. He maps out these scenarios across several tabs of the spreadsheet. “Usually by the third or fourth sheet we have stuff nailed down and know where we’ll get the parts from, then we’ll have how much it looks like if we order 1,000 or 2,000 or 10,000, and we go with the lowest production number, usually 1,000 or 500.”

Though Kickstarter encourages creators to pay themselves for their work, Levy and Wang say they rarely formalize that into their budget. “It ends up being that any margin left goes back into our studio,” Levy says. “We have a margin for error, for if stuff goes wrong, and that comes out of what goes back to our studio after.” That being said, they aim to set the retail price at four times the cost of goods, though they don’t always quite get there, and their Kickstarter rewards are typically discounted 10 to 20 percent below retail.

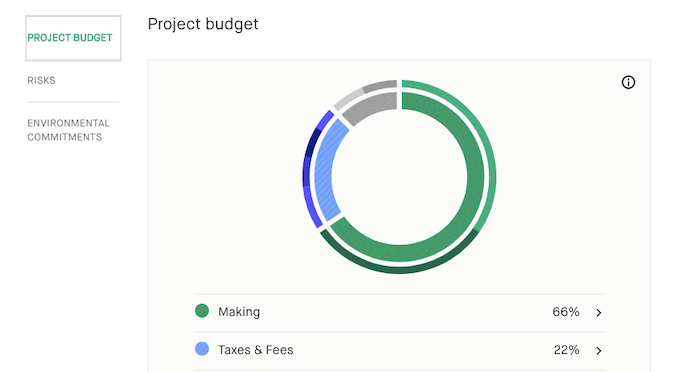

The Herring Blade was their first project to use Kickstarter’s new Project Budget to show backers a broad brush stroke look at their budgeting. It doesn’t have nearly the fidelity their internal planning docs do, but it helps their backers understand the cost of their work.

The Campaign Prep

CW&T’s product development prep ranges from a few weeks to several years. Anything with electronics involved will fall in the longer side of that spectrum, and a friend who specializes in electronics will help get the prototypes production-ready.

Once they feel ready to launch a Kickstarter campaign, that setup takes about one intense week of work. CW&T don’t hire an agency or crew, and they typically shoot and edit their own videos in about two days.

The Communication and PR Strategy

To promote campaigns, Levy and Wang mostly rely on their email list (of about 7,000) and Instagram (where they have about 10,000 followers).

“We’ve started growing our Instagram following with really inexpensive ads,” Levy says. “It doesn’t necessarily have to cost that much, and it’s really low-hanging fruit. If you’re posting stuff, you may as well promote it a little bit and see how posts perform. But we should be constantly trying to grow our email list, too, which we’re not.”

That’s partly because their first Kickstarter campaign earned them more than 4,000 backers, and almost half of their backers are repeat supporters. But even if CW&T are not actively pushing for new signups, they keep in touch with their existing readers. Sometimes a few weeks, even months, will go by between sends, but Levy in particular works to keep the conversation going.

“Our emails are kind of random,” she says. But that might be part of their appeal. “I don’t love writing them, so I’m always shaking it up to try to make it more fun for myself. Sometimes we'll include a little personal anecdote about a cool book that our kids like that week, or a game, or maybe we stumbled across something interesting on the internet that's stuck in our brains, or we watched a good show, or read an interesting book.”

When they’re in campaign mode, they’re more strategic, and use custom referral tags they generate in their Kickstarter Creator Dashboard to track how their backings-focused emails perform. On the Herring Blade project, for example, 30 percent of their backings came from these tagged emails. Kickstarter promotions drove another 51 percent, and the remaining 19 percent came from direct searches, shares, or other types of untagged links.

CW&T keep the communication going as they fulfill the campaign, too. Manufacturing on their first project, Pen Type-A, got seriously delayed, but the couple dutifully continued their project updates. “It’s embarrassing to write those emails,” Wang says, “but it’s always good to write those updates.” That first (and only) rough campaign helped form their commitment to regular communication through the entire process. Other creators inspire them, too. “Scott Thrift has the best policy,” she says, “he predetermines when you’ll hear from him and he sticks to that, so there’s an agreed-upon expectation.”

The Rewards Strategy

“We think of Kickstarter as a launching platform,” Wang says. “We are established enough that we could just put short-run products on a website—and sometimes we do. But Kickstarter is great for making momentum behind a product.”

Though Kickstarter creators can give themselves as many as 60 days to reach their funding goals, most CW&T campaigns run about 30—they find a fast-approaching deadline gets backers on board.

Simplicity helps, too. “The main reason we keep our rewards so simple is because it’s pretty hard to understand the concept if you make it any more complicated,” Levy says.

Most CW&T projects offer just one product, maybe in a few different quantities across reward tiers. Levy points out that this is in part a limitation in Kickstarter’s platform: We’re emphatically not a store, and trying to promote many different products can confuse backers. (Our add-ons feature, however, should make it easier to offer a few different rewards within one campaign.)

Partnerships

CW&T doesn’t do many collaborations, but has learned over a few trial runs that, when you do, it’s important to really coordinate and communicate budgets. Even if you’re aligned on production costs, an external partner might spend much more than you planned on promotion—and expect you to chip in equally.

So on more recent collaborations, like their design work for repeat creator Scott Thrift, they wrote out a contract and clarified they’re supporting his project with design work, not co-producing it. “Having a clear-cut relationship like that just works better,” Wang says.

The Outcome

“Kickstarter has made our practice possible,” Levy says. “It's mitigated the risk involved in launching a new thing and made sure that we're not producing stuff that is wasteful, that nobody's going to want.”

“Our studio would not exist without Kickstarter,” Wang says. Their first campaign allowed them to transition from making software for clients to making design objects for their fans. “It’s hard to beat being your own boss and making the things you want and surviving on it.”

They’re also intentionally staying small and nimble. “I think maybe one difference between the way we treat Kickstarter and other studios potentially is we're not trying to grow our company,” Wang says. “We’re not adding employees or anything like that. We really just want to keep doing what we're currently doing, and Kickstarter has been a great way to sustain that. You don't have to grow into a huge company, we don't want to outgrow Kickstarter. We just want to keep doing this.”